Frank Auerbach’s portraits and landscapes have invited regular comparison with Old Master painting but the full extent of his study of the great compositions of history will not have been recognised before a new exhibition which is opening at the National Gallery, in London.

With the subsidiary title of Working after the Old Masters, the exhibition fits into a series of new initiatives which, like Time Machine mounted in the Egyptian Galleries of the British Museum at the end of last year, seek to invigorate permanent collections of historical material with the tang of contemporary art. In so doing they marry audiences of different tastes and widen their range of interests.

Frank Auerbach, Drawing after Bellini's "The Agony in the Garden", 1987 Photo: The National Gallery, London

The present exhibition includes six oil or acrylic paintings which are based on compositions by Titian, Rubens and Rembrandt owned by the National Gallery, and nearly 130 small drawings in pencil, crayon and coloured felt pen created during the artist’s intermittent visits to the museum. Auerbach has been making such drawings since the beginning of his career and now, depending upon his commitments with his models, prefers to make his visits in the evening when he will not be distracted by a crowd of spectators.

The list of artists who have engaged his attention covers all the schools which a contemporary master of expressionism would be expected to appreciate: Tintoretto, Veronese and the Venetian painters, Frans Hals, Constable and Degas. But there are surprises, too. We might not have expected Auerbach to be engaged by Signorelli’s Circumcision, which is, admittedly, the only Quattrocento composition to have invited his scrutiny; nor Seurat, whose Baignade he appears to have drawn with some regularity.

The key to understanding Auerbach’s choice of artists lies in his motives for making these sketches. They are not sources for his own compositions but assist him in solving compositional problems. He is quoted in the catalogue accompanying the exhibition as saying, “I’ve drawn landscapes to help me with a portrait head, and I’ve drawn from portraits to help me with a landscape. I’m not copying a picture, I’m trying to gain some sort of inspiration from the fact that somebody’s succeeded in grasping something that seems relevant, where I have at that point failed to grasp it in my own picture”.

Frank Auerbach, Drawing after Rembrandt's "Portrait of Margaretha de Geer", 1981 Photo: The National Gallery, London

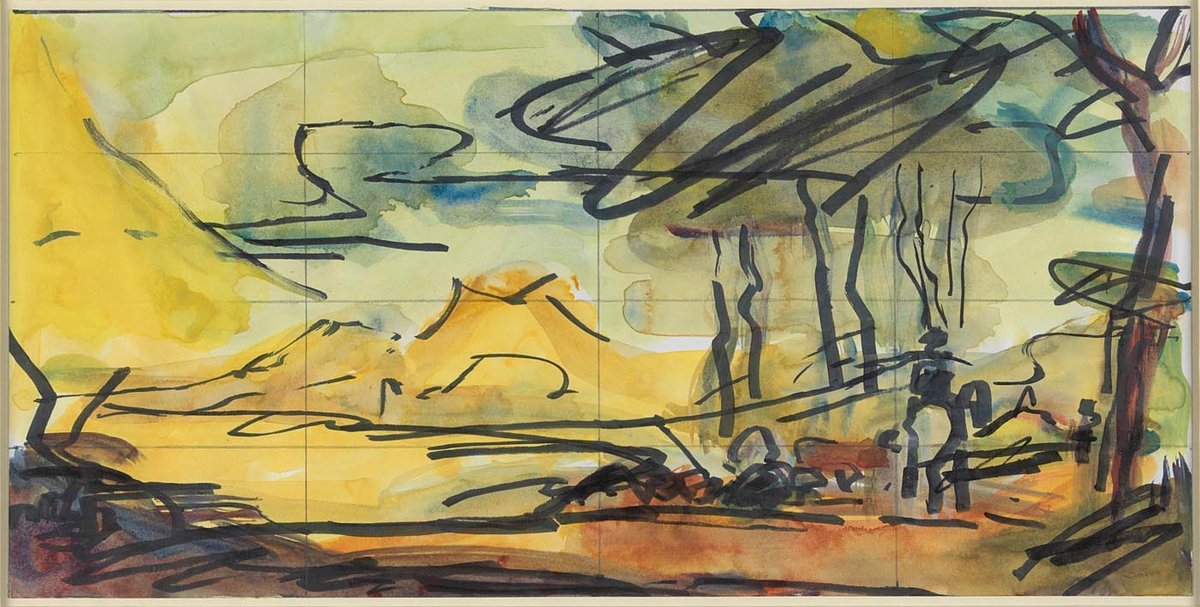

Auerbach’s career as a painter has been punctuated by occasional copies or transcriptions of Old Master pictures. But such is the process of transformation which takes place during their execution that they end up resembling his own landscape or figure paintings more closely than the compositions upon which they were based. Colin Wiggins of the National Gallery’s Educational Department, who has curated the exhibition, describes them as “portraits” of the paintings which inspired them. The grandest interpretations are After Rubens’s Samson and Delilah (1993, Marlborough Fine Art), and After Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne (1971, Tate Gallery), both of which require careful visual excavation before the links with the original paintings are discovered.

This last work was one of four pictures painted to an unusual commission from the British collector David Wilkie, who bequeathed his collection to the Tate Gallery where it was shown in a special exhibition exactly a year ago. Robert Hughes discusses the commission in chapter ten of his monograph of Frank Auerbach (Thames and Hudson, 1990) and explains that it was propelled by Mr Wilkie’s passion for Titian’s art.

Frank Auerbach, Drawing after Caravaggio's "The Supper at Emmaus", 1984 Photo: The National Gallery, London

The commission was launched with two versions of Titian’s Tarquin and Lucretia (1965), which Auerbach based upon the modello in Vienna rather than the celebrated painting in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge; continued with an entirely invented composition, The Origin of the Great Bear (1968), which Auerbach believed Titian might have painted; and completed with two pictures entitled Rimbaud (1976-77) in which, with uncharacteristic eccentricity, the artist inserted a portrait of the French poet into the altar of Bernini’s Cornaro family chapel in place of The Ecstasy of St Theresa.

Frank Auerbach and the National Gallery: Working After the Masters, National Gallery, London, 19 July-17 September 1995.